The Beast of Gévaudan (French: La Bête du Gévaudan; IPA: [la bɛːt dy ʒevodɑ̃],Occitan: La Bèstia

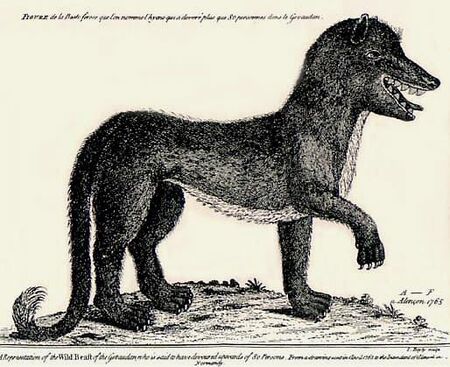

Artist's interpretation.

de Gavaudan) is the historical name associated with the man-eating wolf-like animals which terrorized the former province of Gévaudan (modern day département of Lozère and part of Haute-Loire), in the Margeride Mountains in south-central France between 1764 and 1770. The attacks, which covered an area stretching 90 by 80 kilometres (56 by 50 mi), were said to have been committed by beasts that had formidable teeth and immense tails according to contemporary eye-witnesses. Victims were often killed by having their throats torn out. The French government used a considerable amount of manpower and money to hunt the animals; including the resources of several nobles, the army, civilians, and a number of royal huntsmen.

The number of victims differs according to sources. In 1987, one study estimated there had been 210 attacks; resulting in 113 deaths and 49 injuries; 98 of the victims killed were partly eaten. However other sources claim it killed between 60 to 100 adults and children, as well as injuring more than 30.

The beast was said to look like a wolf but about as big as a cow. It had a large dog-like head with small straight ears, a wide chest, and a large mouth which exposed very large teeth. The claws on its feet were as sharp as razors. The beast's fur was said to be red in color but its back was streaked with black. It was also said to have quite an unpleasant odor.

The Beast of Gévaudan carried out its first recorded attack in the early summer of 1764. A young woman, who was tending cattle in the Mercoire forest near Langogne in the eastern part of Gévaudan, saw the beast come at her. However the bulls in the herd charged the beast keeping it at bay, they then drove it off after it attacked a second time. Shortly afterwards the first official victim of the beast was recorded; 40-year-old Emmet Mardén was killed near the village of Les Hubacs near the town of Langogne.

Over the latter months of 1764, more attacks were reported throughout the region. Very soon terror had gripped the populace because the beast was repeatedly preying on lone men, women and children as they tended livestock in the forests around Gévaudan. Reports note that the beast seemed to only target the victim's head or neck regions; the bites were not to the arms and legs - the usual body parts favored by known predators such as wolves - making the woundings unusual.

By late December 1764 rumours had begun circulating that there may be a pair of beasts behind the killings. This was because there had been such a high number of attacks in such a short space of time, many had appeared to have been recorded and reported at the same time. Some contemporary accounts suggest the creature had been seen with another such animal, while others thought the beast was with its young.

On January 12, 1765, Jacques Portefaix and seven friends were attacked by the Beast. After several attacks, they drove it away by staying grouped together. The encounter eventually came to the attention of Louis XV who awarded 300 livres to Portefaix and another 350 livres to be shared among his companions. The king also directed that Portefaix be educated at the state's expense. He then decreed that the French state would help find and kill the beast.

Three weeks later Louis XV sent two professional wolf-hunters, Jean Charles Marc Antoine Vaumesle d'Enneval and his son Jean-François, to Gévaudan. They arrived inClermont-Ferrand on February 17, 1765, bringing with them eight bloodhounds which had been trained in wolf-hunting. Over the next four months the pair hunted for Eurasian wolves believing them to be the beast. However as the attacks continued, they were replaced in June 1765 by François Antoine (also wrongly named Antoine de Beauterne), the king's harquebus bearer and Lieutenant of the Hunt who arrived in Le Malzieu on June 22.

By September 21, 1767, Antoine had killed his third large grey wolf measuring 80 cm (31 in) high, 1.7 m (5 ft 7 in) long, and weighing 60 kilograms (130 lb). The wolf, which was named Le Loup de Chazes after the nearby Abbaye des Chazes, was said to have been quite large for a wolf. Antoine officially stated: "We declare by the present report signed from our hand, we never saw a big wolf that could be compared to this one. Which is why we estimate this could be the fearsome beast that caused so much damage." The animal was further identified as the culprit by attack survivors who recognized the scars on its body inflicted by victims defending themselves. The wolf was stuffed and sent to Versailles where Antoine was received as a hero, receiving a large sum of money as well as titles and awards.

However on December 2, 1769, another beast severely injured two men. A dozen more deaths are reported to have followed attacks by the la Besseyre Saint Mary

The killing of the creature that eventually marked the end of the attacks is credited to a local hunter named Jean Chastel. He is said to have slain the beast at the Sogne d'Auvers on June 19, 1770. But controversy surrounds Chastel's account. Family tradition claimed that, when part of a large hunting party, he sat down to read the Bible and pray. During one of the prayers the creature came into sight, staring at Chastel, who finished his prayer before shooting the beast. This would have been aberrantbehavior for the beast, as it would usually attack on sight. Some believe this is proof Chastel participated with the beast, or even that he had trained it. However, the story of the prayer may simply have been invented out of religious or romantic motives. Writers later introduced the idea that Chastel shot the creature with a blessed silver bullet of his own manufacture and upon being opened, the animal's stomach was shown to contain human remains.

Since the late 18th century, numerous explanations have been promulgated as to the exact identity of the beast. However none of the theories have been scientifically proven. Suggestions as to what sort of cryptid animals roamed Gévaudan have ranged from exaggerated accounts of wolf attacks, to the myths of

The beast has been recorded in history forever with this statue.

the werewolf, or even a punishment from God. Modern theorists now propose the beasts were some type of domestic dog or a wolf-dog hybrid on account of their large size and unusual coloration. In 2001 a French naturalistproposed that the red-colored mastiff belonging to Jean Chastel sired the beast and its resistance to bullets may have been due to it wearing the armoured hide of a young boar thus also accounting for the unusual colour. Hyenas could not be the culprits, as the beast had a bite of 42 teeth while hyenas only have 34. Other theories include:

- In 1991, Wolf-Hunting in France in the Reign of Louis XV: The Beast of the Gévaudan contended that there can be satisfactory explanations based on large wolves for all the Beast's depredations.

- In 2011, Monsters of the Gévaudan, suggests that the deaths attributed to a beast were more likely the work of a number of wolves or packs of wolves.

- An unknown beast prefers the taste of human flesh, killing over 100 villagers in the South of France. Tens of thousands of citizens scoured the forests and country side looking for the beast out of fear that they could be it's next meal, but with no success.The Beast of Gévaudan made a recent appearance in French movie Brotherhood of the Wolf, generating a new interest in the 250-year-old tale. The beast appeared as the ominous offspring of a lion, supplemented with armor and spiked facial implants.

What (or who) is behind these tales of terror and mutilation in 18th Century France? An examination of period lore is interesting and questionable at best, but a University of North Carolina Professor turned an academic eye to the origin and makeup of the beast in a recent academic text.

The top image is an artist's rendition of a creature, fitting parts of the description of the Beast of Gévaudan.

Muddled Descriptions Records claim that the Beast of Gévaudan attacked at least 162 humans and killed 113around a small town in the South of France 1764 to 1767. Those who survived the attacks gave a wild range of descriptions, with this combination of traits observed in the beast:

The Beast is a quadruped about the size of a horse. It reminds witnesses of a bear, hyena, wolf and panther all at once. It has a long wolf-like or pig-like snout, lined with large teeth. [...] The tail somewhat resembles the long tail of a panther, but it is so thick and strong that the Beast uses it as a weapon, knocking men and animals down with it.

The description, in parts, fits for a wolf, hyena, bear, or panther, but the combined details fail to describe a single known creature. The Beast of Gévaudan issuggested by modern cryptozoologists to be a mutated bear, wolf-dog hybrid, or a species of long extinct form of mesonychid.Mesonychids are a group of predatory Paleocene mammals featuring a skull similar to a hyena's, but a body about the size of a horse. This would place the Beast of Gévaudan in the realm of the Loch Ness Monster – a time displaced, but real creature.

King Louis XV (whose poor choices laid the groundwork for the French revolution) quickly sent professional hunters into the woods of Gévaudan to track down the beast. That's a bit like President Obama sending out Seal Team Six to go after the Mothman. Louis XV also rewarded survivors of attacks, including a group of 8 to 14 year old children who fought off the beast with iron tipped spears.

Hunters devised a series of weapons to defeat the beast, including a maniacal weapon of beast destruction featuring 30 shotguns tied to 30 ropes, with the ropes tied to a six month old calf set as bait for the beast. Poor calf.

Jean-Baptiste Duhamel, a dragoon captain stationed near Gévaudan, mustered up a force of 20,000 plus citizens to search for the beast, with no success. Duhamel communicated closely with Courrier d'Avignon, the only newspaper in the area, exacerbating fear of the creature and circulating renditions of the beast in print. François Antoine, the royal gun bearer, succeeded in tracking down and killing a creature in 1775, returning the six foot lupine for display in Versailles.

Despite Antoine's success, attacks continued, disgracing Louis XV and French forces. A second kill is attributed to Jean Chastel, a local hunter, in 1767. The beast's stomach contained the rotten remains of a human. The legend of Chastel grew to play a vital role in werewolf mythology, with French novelist Abel Chevalley suggesting Chastel used a silver bullet to make the kill.

Folklore surrounding the Beast of Gévaudan became tarnished when multiple creatures met death while attacks on humans continued. Jay M. Smith, a Professor of History at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, pointed an academic eye at the tale in Monsters of the Gévaudan.

Dr. Smith suggests that Jean-Baptiste Duhamel played a large role in stirring up fear surrounding the beast, with Duhamel calling the Beast of Gévaudan a sign of God's anger with the people of France. Duhamel's reasoning for sensationalizing the beast stems from adesire to recoup honor from numerous defeats during the the Seven Years' War. Professor Smith concludes that the Beast of Gévaudan is not a single creature, but a name given to a collection of wolves in the area.